Rationale

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a common cause of morbidity and mortality.(1) The annual VTE event rate is approximately 142 per 100,000 persons.(2) Moreover, patients with VTE are susceptible to the development of long-term complications such as recurrent VTE, post-thrombotic syndromes or cardiopulmonary dysfunction and/or reduced exercise tolerance.(2) The effectiveness of warfarin in preventing and reducing the occurrence of thromboembolic events is well established.(3-6) Despite its effectiveness, warfarin has many drug-drug interactions. Of them, warfarin and acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) is one of the most important due to the widespread use and prolonged effect of aspirin.(6)

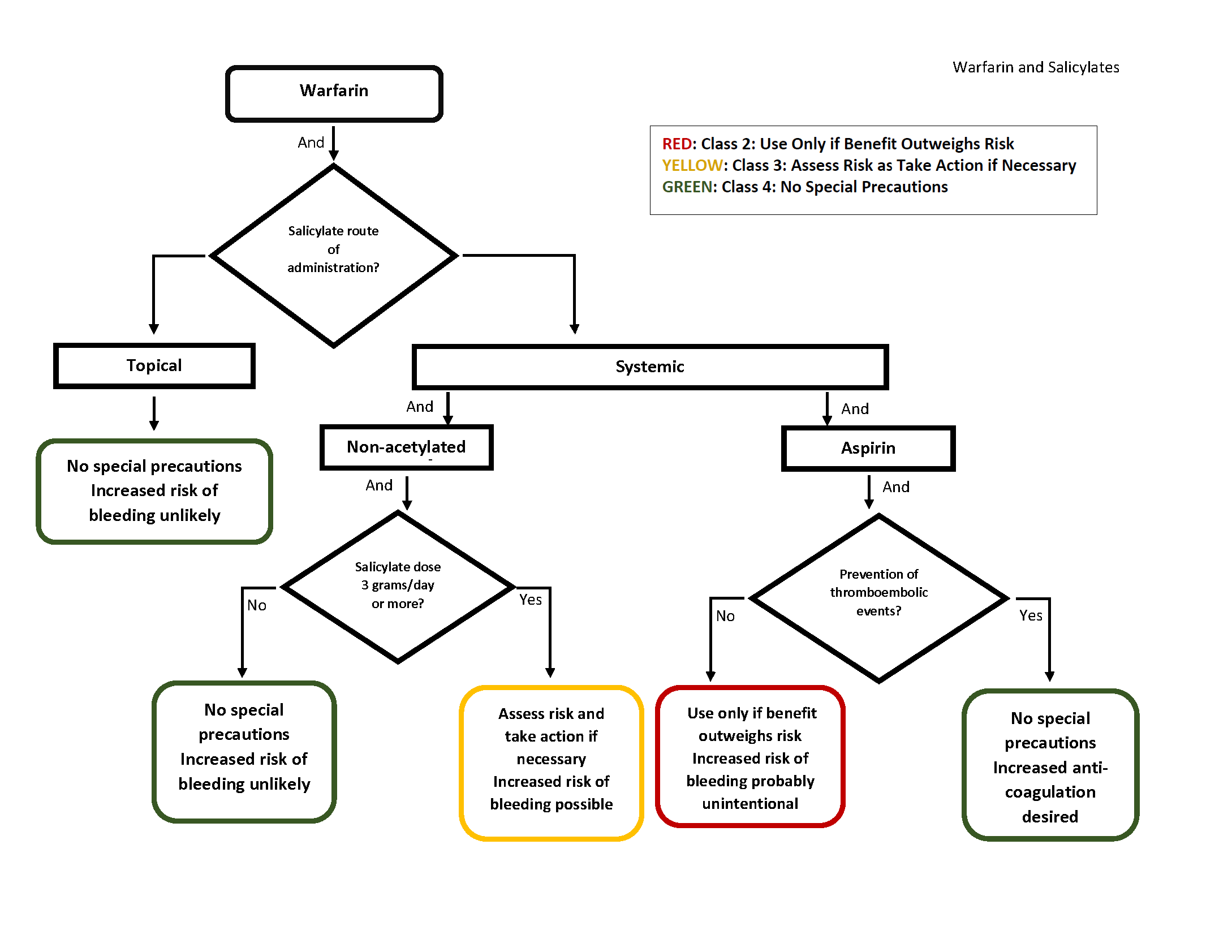

Not all salicylates pose the same risk. Methylsalicylate, an active ingredient in many topical analgesic preparations, is used for pain reduction for musculoskeletal disorders.(7) When used in therapeutic doses, it is not expected to interact with warfarin due the lack of antiplatelet effects.(8) However, when used in extremely high amounts, serum concentrations of methylsalicylate may increase INR.(7, 9-14)

Algorithm

Explanation

Warfarin is a vitamin K antagonist, which competitively inhibits a series of coagulation factors, as well as proteins C and S.(15) These factors are biologically activated by the addition of carboxyl groups depending on vitamin K.(15) Warfarin competitively inhibits this chemical reaction, thus depleting functional vitamin K reserves reducing the synthesis of active coagulation factors.(15)

Aspirin irreversibly inhibited prostaglandin G/H synthase through acetylation of Ser529 of the enzyme in the platelets, consequently prevented thromboxane A2 and prostacyclin formation.(16) Thromboxane A2 is a platelet agonist,(16, 17) whereas prostacyclin stimulates production vascular endothelium.(16) Aspirin’s antiplatelet action does not appear to be dose-dependent;(8, 18) and the low dose (75-100 mg) of aspirin appeared to effectively inhibit the production of thromboxane while preserving prostacyclin production.(8, 16, 19, 20) However, the risk of gastrointestinal irritation and hemorrhage associated with aspirin seemed to be dosed dependent. (21) Therefore, there is probably no additional antithrombotic benefit, but an increased risk of bleeding when using aspirin doses higher than 75-100 mg.

Warfarin and aspirin independently increase the risk of bleeding. The use of warfarin monotherapy and low-dose aspirin monotherapy increased the risk for gastrointestinal bleeding by 4.3,(22) and 3.1-fold, respectively, compared to placebo.(23) The risk of major bleeding for warfarin plus aspirin was 2.5-fold greater than aspirin alone.(24) A prospective cohort study showed that gastrointestinal bleeding occurred more frequently in patients who used low-dose aspirin plus warfarin compared to placebo with an odds ratio of 3.6 (95% CI, 1.7 to 8.9, p=0.0021) after adjusting for age, sex, and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). (25) Another retrospective case-control study found the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was significantly greater in patients taking warfarin plus aspirin compared to patients taking no medication with an odds ratio of 6.7 (95% CI 4.3 to 9.9).(26)

Aspirin may increase the bleeding risk when combined with warfarin.(25) Nonetheless, warfarin and aspirin are used intentionally in many patients for their additive anticoagulant effects.(27, 28) Dual use is common in high-risk populations such as patients with heart-valve replacement who have experienced a major systemic embolism (about 2-3% per year) despite using anticoagulants.(19) The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/ AHA) guidelines recommended a combination of low dose aspirin (75-100 mg) and warfarin in patients with a mechanical prosthesis valve, a bioprosthetic aortic or mitral valve.(29) There is also robust evidence demonstrated the significantly greater reduction in major systemic embolism and mortality in mechanical heart valves patients who were treated with the combination of low dose aspirin and warfarin compared to patients treated with warfarin monotherapy.(19, 30, 31) Combination therapy for this population is appropriate because the benefits appear to outweigh risk of bleeding.(19, 30, 31)

For patients without significant history of embolism, the use of the combination of aspirin and warfarin is controversial. The ACC/AHA guideline do not provide guidance on the combination of warfarin and aspirin therapy in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation (AF), CAD, or those at high risk for stroke.(29) Multiple studies have demonstrated that warfarin plus aspirin reduced the risk of cardiovascular events (i.e., myocardial infarction, stroke, or death).(32-36) Some experts also suggested that adding aspirin to warfarin might be useful because patients receiving oral anticoagulation therapy frequently have concomitant coronary artery disease (CAD) or are at high risk for stroke.(28). However, some experts do not recommend using aspirin in addition to anticoagulant therapy for primary prevention of CAD, including patients with diabetes.(5) They point to other studies that suggest adding aspirin to warfarin did not reduce the risk of recurrent coronary events or thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation and stable CAD,(37) nor prevent reinfarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death.(38, 39)

Non-acetylated salicylates would not be expected to affect the risk of bleeding because these compounds do not have antiplatelet effects.(8) However, high serum concentrations of salicylates may increase INR. Case studies reported concurrently use of warfarin and topical salicylate in an excessive amount resulted in increased INR and bleeding.(7, 9-14)

Precautions

- Consider using acetaminophen rather than aspirin because aspirin increases the risk of GI hemorrhage in patients on warfarin.(22) Although acetaminophen does not have anti-inflammatory property, it has antipyretic and analgesic properties similar to aspirin.(40) However acetaminophen can increase the anticoagulant effect on warfarin, so monitor the INR if acetaminophen is used in doses over 2 g/day for a multiple days.(41)

- Factors such as GI bleeding within 14 days, recent stroke (within 4 weeks), recent surgery (within 2 weeks), platelets < 75,000/L, and uncontrolled HTN (systolic BP >180 mmHg, diastolic BP >110 mmHg) are considered to significantly increase the risk of bleeding.(1)

Artifacts for implementers

- Click to download a PDF of the flow diagram

- Click to download the computable Drools code and associated OMOP Value sets

- Click to view the warfarin value sets

- Click to view salicylate value sets

- Click to view the aspirin value sets

- Click to view the topical non-acetylated salicylate value sets

- Click to view the non-acetylated salicylate value sets

- Click to add comments or ask questions on the Discussion forum

- (Pending): PDF short implementation guide

Drug interaction algorithm implementation survey

- Click to provide feedback about algorithm implementation

Supporting documentation

References

- Streiff MB, Agnelli G, Connors JM, Crowther M, Eichinger S, Lopes R, et al. Guidance for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41(1):32-67. PMID: 26780738

- Vedantham S, Piazza G, Sista AK, Goldenberg NA. Guidance for the use of thrombolytic therapy for the treatment of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41(1):68-80. PMID: 26780739

- Heneghan C, Alonso-Coello P, Garcia-Alamino JM, Perera R, Meats E, Glasziou P. Self-monitoring of oral anticoagulation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;367(9508):404-11. PMID: 16458764

- Keeling D, Baglin T, Tait C, Watson H, Perry D, Baglin C, et al. Guidelines on oral anticoagulation with warfarin – fourth edition. Br J Haematol. 2011;154(3):311-24. PMID: 21671894

- Witt DM, Clark NP, Kaatz S, Schnurr T, Ansell JE. Guidance for the practical management of warfarin therapy in the treatment of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41(1):187-205. PMID: 26780746

- Ageno W, Gallus AS, Wittkowsky A, Crowther M, Hylek EM, Palareti G. Oral anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e44S-e88S. PMID: 22315269

- Yip AS, Chow WH, Tai YT, Cheung KL. Adverse effect of topical methylsalicylate ointment on warfarin anticoagulation: an unrecognized potential hazard. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66(775):367-9. PMID: 2371186

- Roberts MS, McLeod LJ, Cossum PA, Vial JH. Inhibition of platelet function by a controlled release acetylsalicylic acid formulation–single and chronic dosing studies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;27(1):67-74. PMID: 6436031

- Chan TY. Life-threatening retroperitoneal bleeding due to warfarin-drug interactions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(5):420-2. PMID: 19283775

- Joss JD, LeBlond RF. Potentiation of warfarin anticoagulation associated with topical methyl salicylate. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34(6):729-33. PMID: 10860133

- Tam LS, Chan TY, Leung WK, Critchley JA. Warfarin interactions with Chinese traditional medicines: danshen and methyl salicylate medicated oil. Aust N Z J Med. 1995;25(3):258. PMID: 7487701

- Littleton F, Jr. Warfarin and topical salicylates. Jama. 1990;263(21):2888. PMID: 2338749

- Chow WH, Cheung KL, Ling HM, See T. Potentiation of warfarin anticoagulation by topical methylsalicylate ointment. J R Soc Med. 1989;82(8):501-2. PMID: 2778785

- Ramanathan M. Warfarin–topical salicylate interactions: case reports. Med J Malaysia. 1995;50(3):278-9. PMID: 8926909

- Fawzy AM, Lip GYH. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral anticoagulants used in atrial fibrillation. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15(5):381-98. PMID: 30951640

- Clarke RJ, Mayo G, Price P, FitzGerald GA. Suppression of thromboxane A2 but not of systemic prostacyclin by controlled-release aspirin. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(16):1137-41. PMID: 1891022

- Rucker D, Dhamoon AS. Physiology, Thromboxane A2. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing

StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2019. PMID: 30969639 - Hirsh J, Salzman EW, Harker L, Fuster V, Dalen JE, Cairns JA, et al. Aspirin and other platelet active drugs. Relationship among dose, effectiveness, and side effects. Chest. 1989;95(2 Suppl):12s-8s. PMID: 2644095

- Turpie AG, Gent M, Laupacis A, Latour Y, Gunstensen J, Basile F, et al. A comparison of aspirin with placebo in patients treated with warfarin after heart-valve replacement. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(8):524-9. PMID: 8336751

- Herd CM, Rodgers SE, Lloyd JV, Bochner F, Duncan EM, Tunbridge LJ. A dose-ranging study of the antiplatelet effect of enteric coated aspirin in man. Aust N Z J Med. 1987;17(2):195-200. PMID: 3476058

- Hawthorne AB, Mahida YR, Cole AT, Hawkey CJ. Aspirin-induced gastric mucosal damage: prevention by enteric-coating and relation to prostaglandin synthesis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;32(1):77-83. PMID: 1888645

- Chung L, Chakravarty EF, Kearns P, Wang C, Bush TM. Bleeding complications in patients on celecoxib and warfarin. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2005;30(5):471-7. PMID: 16164494

- Masclee GM, Valkhoff VE, Coloma PM, de Ridder M, Romio S, Schuemie MJ, et al. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding from different drug combinations. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(4):784-92.e9; quiz e13-4. PMID: 24937265

- Rothberg MB, Celestin C, Fiore LD, Lawler E, Cook JR. Warfarin plus aspirin after myocardial infarction or the acute coronary syndrome: meta-analysis with estimates of risk and benefit. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(4):241-50. PMID: 16103468

- Hreinsson JP, Palsdottir S, Bjornsson ES. The Association of Drugs With Severity and Specific Causes of Acute Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Prospective Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(5):408-13. MID: 26280706

- Delaney JA, Opatrny L, Brophy JM, Suissa S. Drug drug interactions between antithrombotic medications and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. Cmaj. 2007;177(4):347-51. PMID: 17698822

- Singer DE, Albers GW, Dalen JE, Go AS, Halperin JL, Manning WJ. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126(3 Suppl):429s-56s. PMID: 15383480

- Dentali F, Douketis JD, Lim W, Crowther M. Combined aspirin-oral anticoagulant therapy compared with oral anticoagulant therapy alone among patients at risk for cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(2):117-24. PMID: 17242311

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, 3rd, Fleisher LA, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135(25):e1159-e95. PMID: 28298458

- Pengo V, Palareti G, Cucchini U, Molinatti M, Del Bono R, Baudo F, et al. Low-intensity oral anticoagulant plus low-dose aspirin during the first six months versus standard-intensity oral anticoagulant therapy after mechanical heart valve replacement: a pilot study of low-intensity warfarin and aspirin in cardiac prostheses (LIWACAP). Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2007;13(3):241-8. PMID: 17636186

- Dong MF, Ma ZS, Ma SJ, Chai SD, Tang PZ, Yao DK, et al. Anticoagulation therapy with combined low dose aspirin and warfarin following mechanical heart valve replacement. Thromb Res. 2011;128(5):e91-4. PMID: 17636186

- van Es RF, Jonker JJ, Verheugt FW, Deckers JW, Grobbee DE. Aspirin and coumadin after acute coronary syndromes (the ASPECT-2 study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9327):109-13. PMID: 12126819

- Brouwer MA, van den Bergh PJ, Aengevaeren WR, Veen G, Luijten HE, Hertzberger DP, et al. Aspirin plus coumarin versus aspirin alone in the prevention of reocclusion after fibrinolysis for acute myocardial infarction: results of the Antithrombotics in the Prevention of Reocclusion In Coronary Thrombolysis (APRICOT)-2 Trial. Circulation. 2002;106(6):659-65. PMID: 12163424

- Hurlen M, Abdelnoor M, Smith P, Erikssen J, Arnesen H. Warfarin, aspirin, or both after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(13):969-74. PMID: 12324552

- Effects of long-term, moderate-intensity oral anticoagulation in addition to aspirin in unstable angina. The Organization to Assess Strategies for Ischemic Syndromes (OASIS) Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(2):475-84. PMID: 11216966

- Thrombosis prevention trial: randomised trial of low-intensity oral anticoagulation with warfarin and low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of ischaemic heart disease in men at increased risk. The Medical Research Council’s General Practice Research Framework. Lancet. 1998;351(9098):233-41. PMID: 9457092

- Lamberts M, Gislason GH, Lip GY, Lassen JF, Olesen JB, Mikkelsen AP, et al. Antiplatelet therapy for stable coronary artery disease in atrial fibrillation patients taking an oral anticoagulant: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2014;129(15):1577-85. PMID: 24470482

- Randomised double-blind trial of fixed low-dose warfarin with aspirin after myocardial infarction. Coumadin Aspirin Reinfarction Study (CARS) Investigators. Lancet. 1997;350(9075):389-96. PMID: 9259652

- Fiore LD, Ezekowitz MD, Brophy MT, Lu D, Sacco J, Peduzzi P. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program Clinical Trial comparing combined warfarin and aspirin with aspirin alone in survivors of acute myocardial infarction: primary results of the CHAMP study. Circulation. 2002;105(5):557-63. PMID: 11827919

- Simmons DL, Wagner D, Westover K. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, cyclooxygenase 2, and fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31 Suppl 5:S211-8. PMID: 11113025

- Gebauer MG, Nyfort-Hansen K, Henschke PJ, Gallus AS. Warfarin and acetaminophen interaction. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(1):109-12. PMID: 12523469

Creation and Revision Dates

Created: 11/1/2019Last revision: 11/1/2019